Game Forum: Night in the Woods design review

June 17th, 2018

On the surface, Night in the Woods could easily be mistaken for a simple but cute 2D platformer - there are a host of charming anthropomorphic characters, a hauntingly beautiful electronic soundtrack, and bright environments that evoke memories of 90s cartoons. Within moments of starting the game however, it's clear that there is so much more bubbling underneath. Night in the Woods tells a deeply realistic, personal and relatable story about normal people - who just happen to be animals - with a host of gameplay systems that support and encourage players to explore and experience the world.

Night in the Woods revolves around Mae Borowski, a 20-year old college dropout, and her friends in the hometown she has returned to.

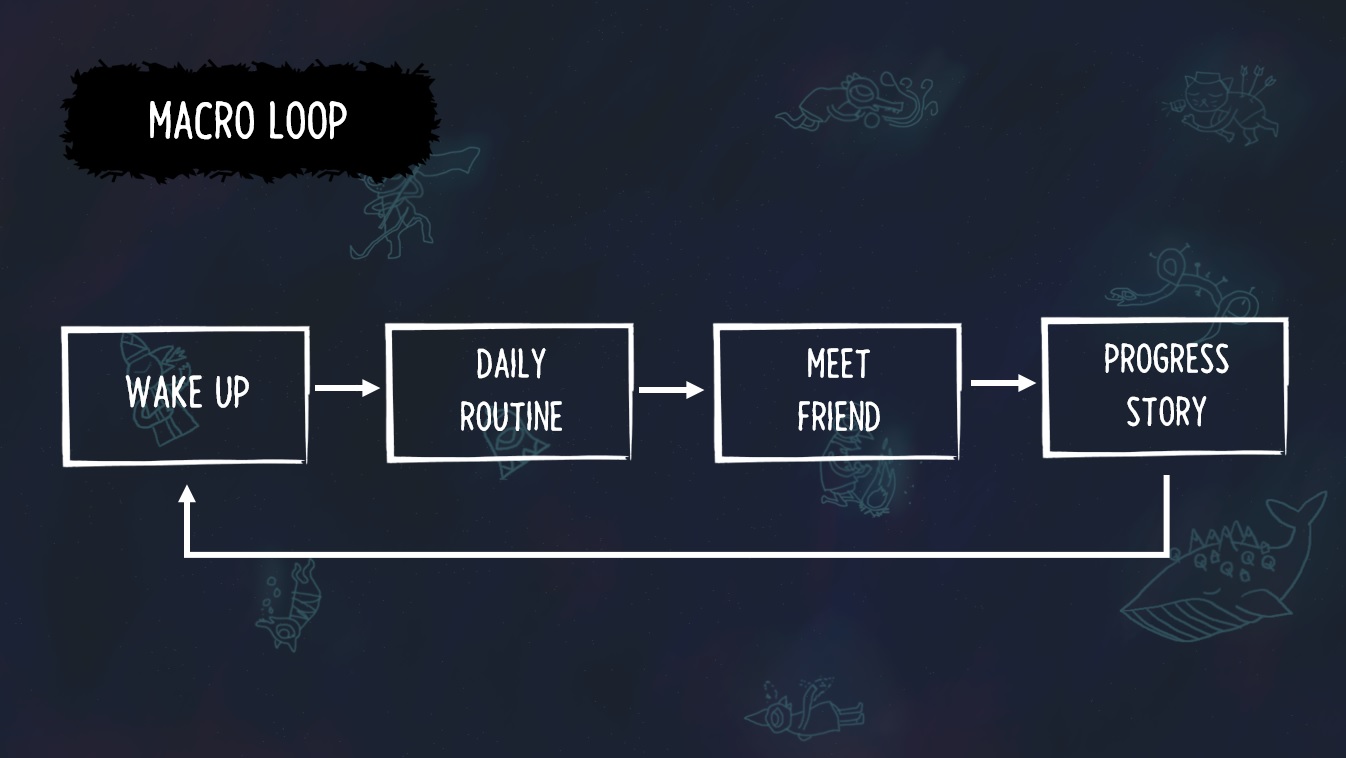

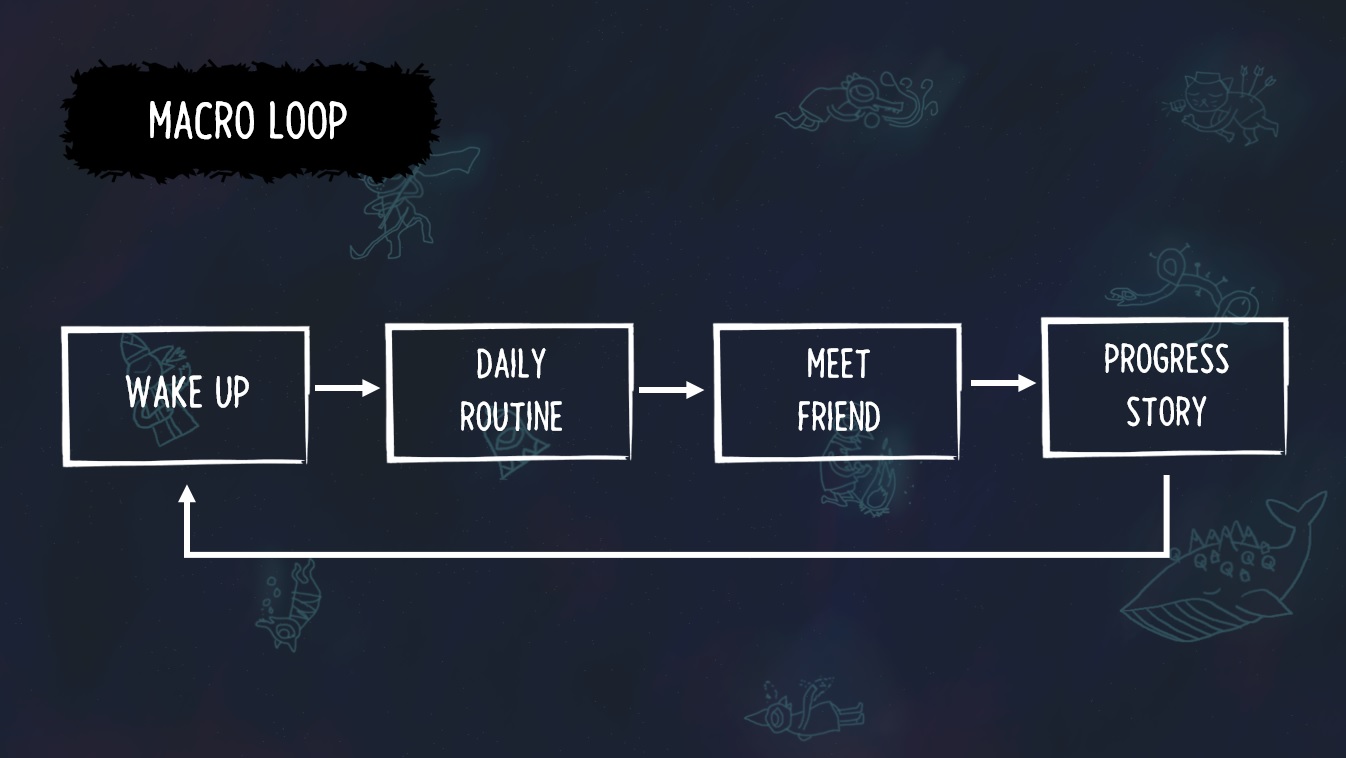

Much of the game follows Mae’s routine. Each day she wanders aimlessly around the same streets of Possum Springs. Around the town are opportunities to explore, whether it’s interacting with objects, traversing to the rooftops, or talking to the townsfolk.

The core loop of Night in the Woods

Interaction points are signalled throughout the world with spatial UI elements. These may be attached to objects in the environment such as Mae's PC or a notice board beside the subway, or over the heads of characters. The type of activity - look, talk, eavesdrop, enter - is also displayed so the player knows what to expect if they decide to interact.

These interaction points will only appear when the player is within a certain radius of the object or character. This small touch means the player is encouraged to explore – both horizontally and vertically – to see what options are available and where. This mechanic is introduced in the opening minutes of the game and used throughout.

When talking to a character, dialog is displayed in bubbles above their heads. When a choice can be made, this is done via a carousel-like selection box. Making choices within the speech bubbles is a clever design decision, reducing the spatial separation between character and dialog – as opposed to the Telltale-style options displayed on screen. Potential options are often short and limited to two or three, ensuring players shouldn’t struggle to remember the available choices even without showing them all at once. There is also a slight input buffer when a selectable dialog is presented, preventing players from accidentally selecting the first choice automatically.

Examples of how interaction points are displayed in game, and dialog bubbles with two options

The designers give the player as much time to explore as they wish. While some may make a b-line to their friends to progress the main story, others will poke and prod at every area of the game to discover the secrets underneath. Through this, mini-arcs are created, and players who retrace their steps each day are rewarded with continuing storylines. This available depth is never explicitly tutorialised and instead relies on the players own decision to poke. This behaviour is likely familiar to fans of similar games that use narrative choices, from Fallout to Telltale's The Walking Dead, but could be missed by those who are not.

Some of these ‘side stories’ are accessed simply by talking to the same person each day. In most cases you’ll learn more about their lives and struggles, while others will take you on mini-adventures such as hanging out by the train tracks or visiting their family. Others however are more involved and require the player to interact with multiple characters or objects, or visit the right location at the right time.

Whether you choose to engage with Possum Springs and the characters who live there or ignore them completely has little to no impact on the game world (there is one minor scene in the main narrative that pays off some of the longer arcs). The interactions themselves are their own reward and will no doubt satisfy those who took the time to explore them.

Mae's daily routine is broken up with simple platforming. Players can jump on objects in both the foreground and background. In the opening moments of the game the player is introduced to the simple metrics of any object within Mae’s jump height generally being available to climb on. The platforming is very forgiving – the player cannot be injured or die, and it is usually very quick to navigate back to your previous position if you make a mistake. The audio and animations of Mae's jumping, and the feedback from in-world objects such as springy powerlines, make platforming a delight. It's often more fun to hop around rather than simply walking from point A to point B.

An example of Mae's jump trajectory

Platforming also introduces the potential for simple puzzles which challenge the player to get from point A to point B. These are never especially complex but provide a moderate challenge, though some of this feels clunky where platforms require precision that the system doesn’t afford, or where angles and slopes make it tricky to land on the desired platform.

There are moments of ambiguity in the platforming as well. Occasionally it’s not apparent whether something can be jumped on or not, and I experienced this mostly with objects in the background layer. During my playthrough this meant I would usually try just about anything that was within Mae’s jump height to see whether I could land on it or not. It’s difficult to say whether this ambiguity was a deliberate choice to encourage exploration, or a case of a few assets that weren’t as readable as others.

The goal when navigating the town is always to reach one of Mae's three friends to hang out with. Reaching one of them triggers the end of the exploration phase and progresses the main story. Here the game introduces the choice between which friend to spend time with. While the main beats of the story will still play out regardless of who you choose, which friend you spend time with will provide a different experience. These choices will also impact how close you get to your friends, and how they treat you as the game goes on even if this is subtle. Presumably, this decision was to encourage players to replay the game and make different choices the second time through.

Narrative segments are also punctuated with minigames which introduce variety to the gameplay. More often than not these are fun diversions, though some are less successfully. While I really enjoyed the idea behind the sequences where you jam with your band, trying to play bass guitar with the face buttons of a Switch controller is not especially intuitive or comfortable.

The main narrative itself deals with some very real-world issues. Themes such as poverty, sexuality, loss and abuse are commonplace throughout the story and make for some very emotional scenes and conversations. Mental health also forms a significant part of the main story with many characters experiencing issues to some degree.

The game not only handles these topics sensitively, but treats them as a normal part of life. Friends discuss their problems and talk about how they feel, but it is never sensationalised. This is a refreshing change in video games, and something that makes the story linger on long after the game has finished.

Perhaps because the game shines so much in its introspective moments, it's slightly disappointing when the later part of the narrative introduces some Scooby Doo-esque mystery elements. While these do tie into Mae’s personal story in a fairly cohesive way, it feels like an unnecessary diversion after spending so many hours building goodwill and care for the characters. Everyone's opinions will likely be different on this particular point, but personally I would have preferred a story arc more in line with the tone and realism of the early game.

Final Words

Night in the Woods tells a deeply emotional story and, though there are a few minor issues in the platforming and narrative, this never detracts from joy of spending time with Mae and her friends.

The systems in the game provide the tools to allow the player to explore at their own pace, rewarding them for doing so but never punishing them for not. This is supported by platforming which breaks up the monotony of navigating the same areas each day, and also allows for the introduction of puzzles. In all, Night in the Woods is able to craft a story with relatable characters, dealing with themes in a thoughtful and reverent way often not seen in video games.

About the Studio Gobo Game Forum

Each week a member of the design team at Studio Gobo presents a design-focused review of a game of our choice. This gives us the chance to think critically about the games we play and get better at discussing them with others. When it's my turn to present a review, I will also share a blog post covering the key points.